Featured Image by PublicDomainPictures on Pixabay

Do you click hyperlinks? This post is full of them: click them, follow them, read them. Or else search the topics and find links of your own, but get started doing something to learn more.

A year ago, I was reminiscing… three memories: inflation, gold, and a profligate economy founded upon debt, which only sounds like an oxymoron.

One more memory, along those lines. Mid ’70s, probably pre-Star Wars, probably a Saturday, and Grandpa’s over for dinner, always a minor Occasion. With front-door greetings over, coats taken, dogs settled, and drinks well in hand, the family sits together around the living room, as ever talking and remembering and passing the time.

This particular afternoon, though, the tone is vexed… that special incredulity-slash-resignation only politicians can inspire. This afternoon, the value of a dollar or, rather, value past now lost: how much a dollar no longer buys, and the daft decision-makers who don’t or won’t comprehend, much less accept, their own responsibility – not only for here-and-now but come the inevitable reckoning.

Bonus memory… remember this one? Probably from the ’90s… your RSP advisor has you signing a document that reads, Past is no indication of future performance, and while you scrawl, they finish their spiel by saying, “…but historically, the stock market has always tended to rise.” And as far as that was accurate, it was also mere dissembling unless adjusted for inflation.

As snow on the ground is not the weather, ‘rising prices’ are not inflation. As far as inflation is the issue, prices don’t actually rise; rather, the currency’s purchasing power falls, and more dollars must accumulate to buy the same item as before, which seems like prices getting higher but is not the same thing as costs that rise against sound measures.

If today’s runaway inflation has not been headed our way the past fifteen years, then how about the past fifty? A few months after I was born, the 37th US President responded to runaway inflation, which by then of course had been politicised. Two features of his new economic policy were an end to the fixed-exchange currency arrangement, in existence since 1944, which by then of course had been politicised, and a shocking yet not shocking halt to the international convertibility of currencies into US-held gold. Perhaps no shock, none of this is considered among the 37th Administration’s accomplishments, not whether you look here, here, or even here although it is briefly mentioned here.

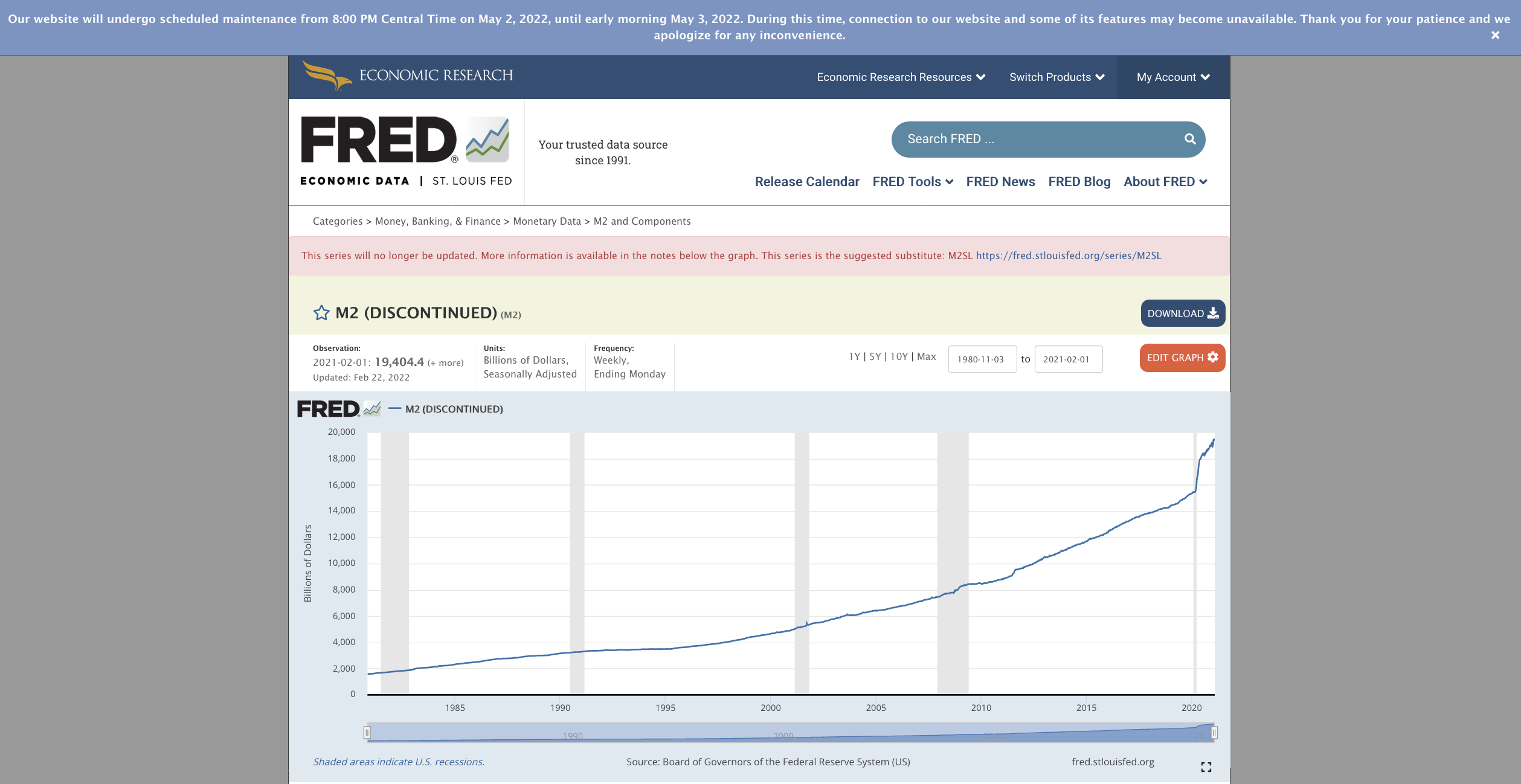

At least grant the past two years… yet the ‘runaway’ bit, now as in the ’70s, is simply the amplified effect of machinations underway for the past 109 years.

Before the Federal Reserve was enacted in 1913, inflation was an expansion of the money supply – these days an increase in the supply of currency units: dollars, renminbi, rupees, whatever. An effect of inflation is a definite fall of purchasing power by dilution of currency units from having created more and more and more of them. Prices ‘rise’ driven by currency debasement, an effect of inflation where prices seem to rise because their numerical values get higher, and people might spend more for the same, or spend less and have less.

Another effect is an expectation everybody gathers for prices to get higher still. Prices ‘getting higher’ vs. prices ‘rising’ is my way to distinguish between what economists say is nominal and what they say is real. Credit the 20th century Fed-era economists, all tied up in knots over the determinants of demand-pull and cost-push and all manner of academic-importance speech, which I guess is the mission-creep you’d need if there were a vacuum of cultural memory that needed filling – as easy as money from thin air, or playing god with people’s lives and livelihoods, or hubris.

How little of this actually is a cultural memory anymore, much less a family one, might be telling. Something I remember my Dad used to say all the time – he said it that Saturday in the living room, and I remember my Grandpa agreed: “It isn’t that people don’t know; they simply don’t want to know.”

There’s a lot riding on partial perspectives – everything, you could say – so, what… let it ride?

Or look into things. More thoroughly, on your own terms, whether you’re curious or not. Suppose you even come to understand the world more than you thought you did, or more than you remembered.