Featured Photo Credit (edited): constantiawork on Pixabay

“Tech [Anything]” grabs attention these days, so don’t be too miffed once you start reading because this is me literally giving it away inside thirty words.

I. Time to Think Differently

Fill the washing machine, add some detergent, set the dial, and push ‘Start’.

It’s a 25min cycle… now, why not grab a coffee, or something to read…

Technology is a marvel… and if there’s one benefit we enjoy, thanks to Technology, you’d have to think it’s surplus time. Take that laundry off your hands, and all that time’s now on your hands.

So close that door behind you, and grab that coffee, and something to read – after all… you are, technically, still ‘doing the laundry’ – we all respect that… why else even invent a washing machine? Listen closely, behind that closed door: can you hear it? That little machine chugging merrily along, doing the laundry while you slip away, guilt-free!

Like I said: Technology is a marvel.

And only a fool would disagree – next time you find yourself faced with doing the laundry, just weigh your surplus time against all that hand-wringing labour … unless, of course, you prefer leaning over a washtub down by the creek, or beating your clothes with a rock.

From delicate hands Technology lifts all the toil we prefer to avoid, and in the process, what we learn while ‘doing the laundry’ is how surplus time is the expectation we once never knew we couldn’t live without. Listen more closely, behind that door, and what you’ll hear is not the intrepid little washing machine but the sterile drone of some finger-raw laundry fool processing their foolish foolishness. But you’re nobody’s fool – you set that dial and went to grab a coffee, and owned that fool in the process.

We seem to shorthand a lot of things this way – or, rather – we seem to invent a lot of Technology that shorthands things for us by compressing something lengthier into a more singular ‘process’… whatever took time over several steps to complete, now just a mere leap ‘from there to there’.

We also seem to talk this way – or, rather – we seem to think this way. For instance, you’ll hear people shorthand their vacation: “We did the Louvre, did the Eiffel Tower, did the whole Paris thing…”

And hey, when you only visit a few days, that means squeezing in as much Paris as you can while you can because, like any process, that ‘vacation’ you start will eventually be coming to an end. Added bonus: back home, when someone asks, “How was your vacation?” you can shorthand the whole trip with that cool touch of insouciance about all the places you “did.”

And sure, maybe this shorthanding is a checklist mentality bereft of politesse, but for anyone who really knows, an embrace of surplus is a sophisticated taste grown accustomed to efficiency. Besides, it wasn’t just anybody who “did Paris,” was it? As they would say in the City of Light: “Comme tu penses, donc tu es.” They’d say it fluently, of course.

As for this post, I’ll grant that a two-sentence leap from laundry to the Louvre is a little abrupt. But if you’re struggling to spot the Technology thread in this Paris bit, that is sort of the point.

Beyond e-devices and microprocessors and the digital stuff typically considered these days to be Technology, think about process and all the simultaneous design and infrastructure we simply take for granted… I mean beyond obvious stuff, like WiFi and satellite communications, or fibre optic networks and transmission towers, or even jet engines and global travel. Think way back. Think like that fish who suddenly notices all the water… but this time, instead of noticing the water, notice how long you’ve been immersed in it.

Take Paris trips and leisure time. Take the whole concept of ‘vacation’, for being a great example of technological surplus. For one thing, ‘vacation’ now means it’s not ironic that hotels, restaurants, and tourism have become an industry unto themselves.

Think past museums and exhibits and architecture… magnificent towers, world cities, global infrastructure… stable governments, world commerce, industrial agriculture, economies of scale… think past all that and, instead, think how all that stuff has developed really gradually over a long, long, long, long time. A long time. Centuries, I mean – not days.

Think how all that stuff had to be rethunk and revised and rebuilt again and again and again through multiple versions and earlier forms in how-many-other-places across Planet Earth – so, think ‘actual history’, the process of life underway. If you can, even think back further than the 21st century – ikr!

Think of the manner by which all our Technology has been developed and refined in dozens of countries by gazillions of people over centuries of accidents and mistakes and trial and error and serendipity. Think about all the discovery and extraction and refinement of raw materials for manufacturing, and all the supply chains that had to be invented from scratch to keep it all circulating, and all the sales and retail and finance that were established, not just to keep all those things viable but supplied and chained in order to be sustained. And think about all the years and decades and centuries of time during which all this came to be. Think about another way to conceive of “technology” – think not “tech” but “-ology” – and think at least once-removed from 21st century glee. As opposed to surplus time, think committed time. Think historical time and geographical time (which would be time- and place-time). If possible, think about all this stuff from any perspective that is beyond your own.

Oh, and think with no defined horizon, no particular pinpoint. As each ‘present moment’ arrives, and moves on, then arrives again, and then again moves on… think process in its most literal ongoing expression: think always now, with due respect for both memory and foresight. Stop thinking about what process means, and start thinking what process is.

All this is probably a lot to think about, but we are nearly done thinking: think how submerged we are in technology, innovation, progress, and euphoria, and commerce and growth and leisure, and the way things are, and the way we want them to be, and the way we’re accustomed to all of them being, all at once even if not all in concert.

… or, failing all that, at least think of our taste for efficiency and our commitment to surplus.

Recap:

(a) Time spent on process? Not on my watch!

… yet for misconstruing ‘steps in a process’ as ‘short-lived times spent on innumerable single events’, each shorthanded process gradually changes our outlook from ‘means as means’ to ‘means becoming ends in themselves’

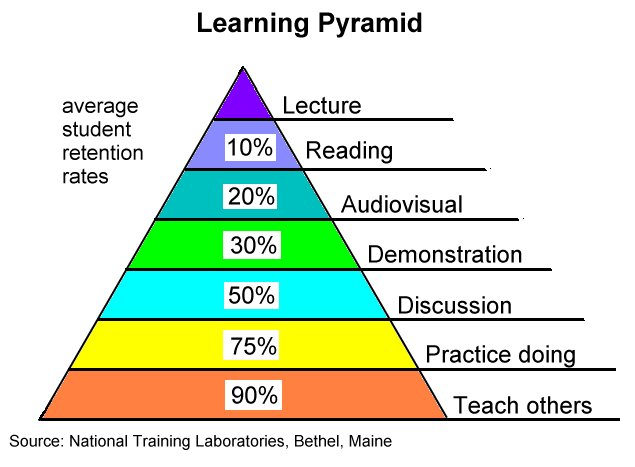

(b) Eureka! Time saved by technology!

… yet for gradual changes to our outlook, ‘surplus time’ has a real effect upon our thinking and, thereby, upon our decisions and behaviour

What I hear called Technology someone else might call “innovation” or “advancement,” or someone else might critique as “progress.” “Pioneering,” “state of the art,” “cutting edge” – all these, also, to the point: as we stake claims of ownership for words and concepts, that seems pretty telling as to how immersed we are, living inside all this. Or maybe better to say how all this lives inside us. And the more immersed it is, the more feverish our yammering becomes: “next level,” “über-sophisticated,” “transcendent.”

We’re soaking in ourselves, it seems, and maybe it’s time for a rinse. And thus do we find our way, in the space of two sentences, back to doing the laundry.

Click here to read Tech Trade-Off: II. Learning to Think Differently

.