Featured Image by Mladifilozof & Aristeas: Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5957893

Click here to read Part I. Language

Something obvious, to start: our use of language directed to others and prompted by others is intended for others and received by others.[1] This is equally plain to see from the Rhetorical WHY’s foundation, the Rhetorical Model of Communication:

- a message-as-conceived and -as-conveyed

- a message-as-received and -as-interpreted

- a message’s connotations and resonance

- small-‘t’ “truth”

Small-‘t’ “truth”[2] at the center denotes the weight of responsibility we bear for our beliefs, the meanings we claim as “true” in the presence of everyone else doing the same thing. Language, then, seems as vital to our common well-being as the air we breathe and the water we drink.[3]

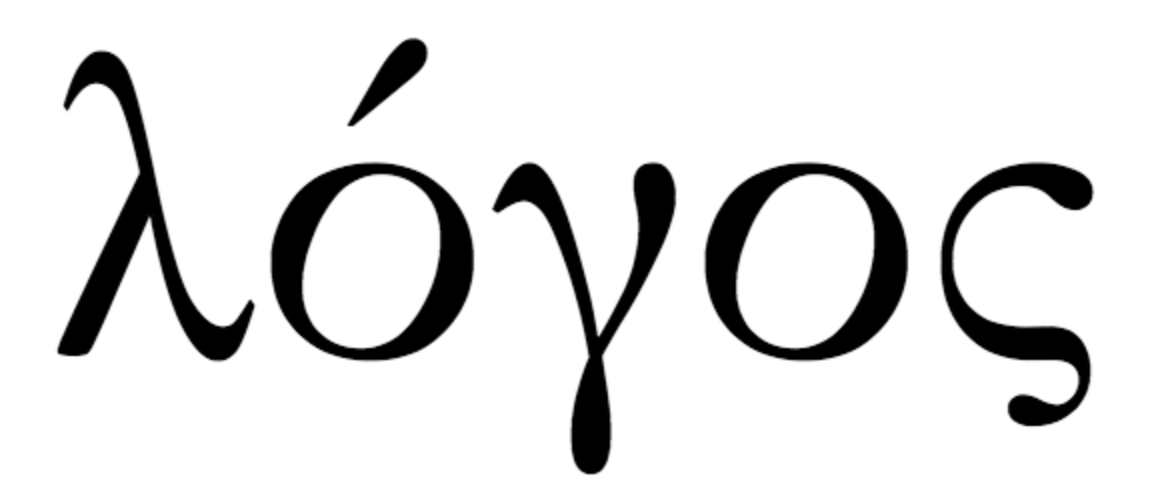

As to Gadamer’s Biblical comparison, introduced in Part I… from the Greek of the New Testament, “Word” translates as λóγος (logos), and language – logos, the Word – within us reflects the imago Dei of Creation. From this root issues a robust etymological lineage: word, speech, discourse, logic, reason, rational thinking – traits in the 21st century that seem so empirical, dependable, reliable, and antithetical to faith. Yet, for having language, we still have no supernatural facility to claim as our own – no omnipotent glory – that might make eternally creative use of it. We have but vaulting ambition – sinful pride – that frustrates our use of what feels somehow essential yet lies somewhere beyond our finite capability.

Thus we misconstrue our essence as instrumentality and our existence as authority… again that hazy distinction between essence and aim: imagine the world where hubris is surpassed only by vanity. We do in fact bicker endlessly over alternative facts, and our shared understanding – a shared estrangement – does in fact increase. And thus (again with added emphasis), in light of Heidegger – in light with Heidegger, in the clearing – I might read the opening verses of the Gospel of John as descriptive and readily spot both real and figurative IB:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning. Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made. In him was life, and that life was the light of all mankind. The light shines in the darkness…

(John 1:1–5)

The darkness is an image also invoked by Taylor, certainly bearing a negative tone, to describe our bids at imposing our own light within Heidegger’s clearing. John counters the darkness with two essential claims: (i) God is logos, and not in some protean way but definitively, while (ii) the Word is the underlying source of ‘making’ and ‘made’, of light and life, with our goodwill or human essence being but an image of His.

One final detail from Arthos is worth adding to this spiritual aspect of IB, for two reasons: first, to credit Gadamer’s “fusion of horizons” as a way to describe IB, and second, to acknowledge Gadamer’s concept of “conversation” as something spontaneous, emergent, and unpredictable. Of the spiritual footing for Gadamer’s hermeneutical approach, Arthos says this:

For Gadamer, Christian incarnation “is strangely different from” the manifestations of pagan gods in human form (TM, 418/WM, 422). In Christology, the spirit made flesh is “not the kind of becoming in which something turns into something else” (TM, 420/WM, 424). This strong enigma places the credal[4] faith apart, and upends the normal relation of the spiritual and the material. The indivisible bond between the word and the person is a fuller ontological relation than simply the unity of the spiritual and material. The relation between word and person is no bloodless, conceptual abstraction. The constancy of the person in the word represents a concentration or fullness of meaning and an increase of being. We can see this, for instance, in the idea of a promise, in which a person stands behind the word that is given, since it is they as much as the word that is at stake, and the fulfillment of the promise strengthens the person who made it and the community it forms. The innovation of the doctrine of the word is to reverse the trend set in motion with the Greeks that the reasoning faculty distills the mind’s work from the accidents of the flesh. Logos is rather the fully embodied medium of human community.

(Arthos, 2009, p. 2)

Earlier in the chapter of Truth and Method that Arthos quotes, Gadamer explains that our diverse world of languages and their associated cultures have this in common: when speaking of the Word, none is able to express its true positive being:

The greater miracle of language lies not in the fact that the Word becomes flesh and emerges in external being, but that that which emerges and externalizes itself in utterance is always already a word.

(Gadamer, 2004, p. 419)

The Word “[being] always already a word” I liken to a simultaneous positive ‘freedom to…‘ and negative ‘freedom from…‘, an autonomy we can observe and describe but not impede or control. This “externality” oddly serves as a great equalizer across cultures, if we let it – that is, if we heed Taylor and seek not “to impose our light [in its place and] close ourselves off to [others]” (Taylor, 2005, p. 448). As compared to something in between us that enjoins, Gadamer describes something among us that joins.

To take all this spiritually, or else not, is up to each person – as apparently it must be. I can only express my words, here and now, for you to take or leave, as you will. Yet this much for all seems undeniable: each one of us might cast our self in this role of creator, as such: “If it were up to me… if I were the one in charge… if only we did things my way… .” Is it little wonder if the world and life and history seem defined by our multitudinous disagreements? And if saying so seems obvious, or pessimistic, consider too that Heidegger’s entire point seems to be an imperative to “Listen,” advice most infamously needed when it’s not happening.

One final analogy for IB departs from philosophy and the spiritual for natural science, which I include here on account of wonder. I take it from physicist Dr. Robbert Dijkgraaf during a 2015 appearance on PBS Nova:

“In this very simple formula, the whole geometry of the universe is hidden.… It’s also a signature formula for Einstein. The true mark of his genius is that he combines two elements that actually live in different universes. The left hand side lives in the world of geometry, of mathematics. The right-hand side lives in the world of physics, of matter and movement. And-- so perhaps the most powerful ingredient of the equation is this very symbol, equals sign, here: these two lines that actually are connecting the two worlds. And it’s quite appropriate they’re two lines because it’s two-way traffic: matter tells space-and-time to curve; space-and-time tells matter to move.

“You know, you have the huge universe, and it obeys certain laws of nature. But where in the universe are these laws actually discovered? Where are they studied? And then you go to this tiny planet, and there’s this one individual, Einstein, who captures it. And now there’s a small group of people walking in his footsteps and trying to push it further. And I often feel, Well, you know, there’s a small part of the universe that actually is reflecting upon itself, that tries to understand itself.”

I can imagine Dijkgraaf granting to Einstein a cosmic generosity, the goodwill to have made room in the clearing for others, e.g. a “small group of people walking in his footsteps.”

Some people get spiritual about cosmology, and physics too, so offering this analogy in the wake of Heidegger’s cosmic spirit seems more à propos than non sequitur. Personally, I think science and spirituality would find plenty to talk about together, if they would willingly join forces and listen to each other, and perceive expressions of interest, and develop some basis of shared understanding.

Besides its temporal implications, the second part of Dijkgraaf’s remark resembles a concept I have elsewhere called mirroring: briefly, an effect of interaction where the response provoked in Person ‘A’ by the prompt of Person ‘B’ serves as a reflection of Person ‘B’, as if Person ‘A’ were a mirror for Person ‘B’ to see themselves. Re-action reflecting action implicates both participants, and of course, the mirroring effect is simultaneously mutual, travelling both ways at once: between people, IB is a compelling imperative to listen and also respond – it suggests our joint interaction. By Dijkgraaf’s Einstein analogy, mirroring might also suggest that equals sign.

In all these concepts of mutual relatedness – philosophical, spiritual, cosmological – IB is a kind of setting, albeit not a literal physical location. Where ‘one’ thing ends and ‘another’ begins is an abstract third space between the two in relation. That said, IB is temporally present – each moment figuratively here and literally now, continuously underway and under continual renovation, forever in adjustment, always resembling, never quite remaining. This third space may overlap, such as when two people share something in common, or it may be a gap, such as when two people have nothing in common. Either way, it’s IB’s dynamic that is defining their relationship.

Click here for Part III. Relationships

[1] By “others,” we might also include “self,” in the more straightforward matter of defining the “audience.”

[2] Subsequently, any resultant small-‘t’ truth offers some capital-‘A’ Assurance, even if capital-‘T’ Truth remains beyond certainty or else relies on some kind of faith. Whether we even call this consensus the capital-‘T’ “Truth” would seem to depend on how well we get along together.

[3] Exactly how Heidegger came to understand language as this vital is the focus of Taylor’s essay although, admittedly, I am still pondering his overall discussion. But, again, I broaden “language” – as well as “text” – to comprise all our communicative efforts, and as I often said to students, “If it’s done by people, it’s rhetoric,” by which I meant, “it’s persuasive,” i.e. it’s something inherently communicative.

[4] An alternative definition for agenda is “things to be done,” originally theological, “matters of practice, as distinguished from belief or theory”; as opposed to credenda “things to be believed, matters of faith, propositions forming or belonging to a system” from which we derive creed. Thus I note with interest Arthos’s reference here to “credal faith.”

5 thoughts on “Conceptualising the In-Between: II. Logos”