Photo by Dave Mullen on Unsplash

We teachers like to talk about teacher stuff, like assessment and curriculum. But shop talk can leave them yawning in the aisles, so sometimes I like to try using analogies. Analogies are great because, since they’re not exact, that can actually help shine more light on what your trying to understand.

Here’s an analogy: I walk into a theatre and sit down behind somebody. Seeing the back of his head, I now know what it looks like – his hairstyle, for instance, or the shape of his head. I have no idea what his face looks like since that I cannot see from behind. Something else I notice is his height – even sitting down, he’s obviously going to block my view of the screen and, since I’ve been waiting a long time to see this movie, I decide to change seats.

So I move ahead into his row. Now I sit almost beside this tall stranger, just a few seats away. Now, from the side, I can see the profile of his face – eyebrows, nose, chin. At one point, he turns to face me, looking out for his friend who went for popcorn, and I can fully take in his face. Now I know what he looks like from the front. Except it’s probably clearer to say, Now I’ve seen him from the front and remember what his face looks like – I make this distinction because it’s not like he turned to look for his friend, then stayed that way. He turned, briefly, then turned back toward the screen, facing forward again, and I’m left seeing his profile once more.

Sitting a few seats away, to say that I know what his profile looks like, side-on, or that I remember what his face looks like, just as I remember what the back of his head looks like – this is probably most accurate. In this theatre situation, nothing’s too hard to remember, anyway, since the whole experience only takes a minute or two and, besides, we’re sitting near enough to remind me of those other views, even though I can only see him from one of three perspectives at a time: either behind, or beside, or facing.

An analogy, remember? This one’s kind of dumb, I guess, but I think it gets the point across. The point I’m comparing is assessment, how we test for stuff we’ve learned.

As I understand the shift from traditional education (positivist knowledge-based curricula, teacher-led instruction, transactional testing) to what’s being called “the New Education” (constructivist student-centred curricula, self-directed students, transformational learning), I’d liken traditional testing to trying to remember what the back of his head looked like after I switched seats. As I say, I might get some clues from his profile while sitting beside him. But once I’m no longer actually sitting behind him, then all I can really do is remember. “What can you remember?” = assessment-of-learning (AoL)

In the New Education, I wouldn’t need to remember the back of his head because that’s probably not what I’d be asked. Where I sit, now, is beside him, so an assessment would account for where I sit now, beside him, not where I used to sit, behind. That makes the assessment task no longer about remembering but more in line with something immediate, something now as I sit beside him, seeing his profile, or during that moment when he turns and I fully see his face. A test might ask me to illustrate what I was thinking or how I was feeling right at that moment. “What are you thinking?” = assessment-for-learning (AfL)

There’s also assessment-as-learning (AaL), which could be me and my friend assessing each other’s reactions, say, as we both watch this tall stranger beside us. In the New Education, AaL is the most valued assessment of all because it places students into a pseudo-teaching role by getting them thinking about how and why assessment is helpful.

When proponents of the New Education talk about authentic learning and real-life problems, what I think they mean – by analogy – are those things staring us in the face. Making something meaningful of my current perspective doesn’t necessarily require me to remember something specific. I might well remember something, but that’s not the test. The New Education is all about now for the future.

In fact, both so-called traditional education and the New Education favour a perspective that gives us some direction, heading into the future: traditional education is about the past perspective, what we remember from where we were then, while the New Education is about the present perspective, what we see now from where we are now. It’s a worthy side note that, traditional and contemporary alike, education is about perspective – where we are and where we focus.

By favouring the past, assessing what we remember, the result is that traditional education implies continuation of the past into the future. Sure, it might pay lip service to the future, but that’s not as potent as what comes about from stressing remembrance of the past. Meanwhile, lying in between, the present is little more than a vehicle or conveyance for getting from back then to later on. You’re only “in the moment,” as it were, as you work to reach that next place. But this is ironic because, as we perceive living and life chronologically, we’re always in the moment, looking back to the past and ahead to the future. So it must seem like the future never arrives – pretty frustrating.

The New Education looks to the future, too, asking us to speculate or imagine from someplace we might later be. But, by favouring the present, assessing what we think and feel, and what we imagine might be, the New Education trades away the frustration of awaiting the future for a more satisfying “living in the moment.” We seem to live in a cultural era right now that really values living in the moment, living for now – whether that’s cause or effect of the New Education, I don’t know. In any case, says the New Education, the future is where we’re headed, and the present is how we’re getting there, so sit back and let’s enjoy the ride.

As it regards the past, the New Education seems to pose at least two different attitudes. First, the New Education seems to embrace the past if that past meets the criterion that it was oppressive and is now in need of restoration. Maybe this is a coincidental occurrence of cultural change and curricular change that happen to suit each other. Or maybe this is what comes of living in the moment, focusing on the here-and-now: we’re able to take stock, assess for the future, and identify things, which have long been one way, that now we feel compelled to change. Second, the New Education seems dismissive of the past. Maybe this is also because of that past oppression, or maybe it’s leftover ill will for traditional education, which is kind of the same thing. What often swings a pendulum is vilification.

Whatever it is, we ought to remember that dismissing the past dismisses our plurality – we are all always only from the past, being ever-present as we are. We can’t time-travel. We are inescapably constrained by the past from the instant we’re born. What has happened is unalterable. The future arrives, and we take it each moment by moment. To dismiss the past is delusory because the past did happen – we exist as living proof.

For all its fondness and all its regret, the past is as undeniable as the future is unavoidable, for all its expectancy and all its anxiety. As we occupy the place we are, here, with the perspective it affords us, now, we need the courage to face the future along with the discipline to contextualise the past. As we live in the moment, we are bound and beholden to all three perspectives – past, present, future. Incidentally, that happens to be where my analogy broke down. In a theatre, we can only sit in one seat at a time. Let’s count our blessings that living and learning offer so much more.

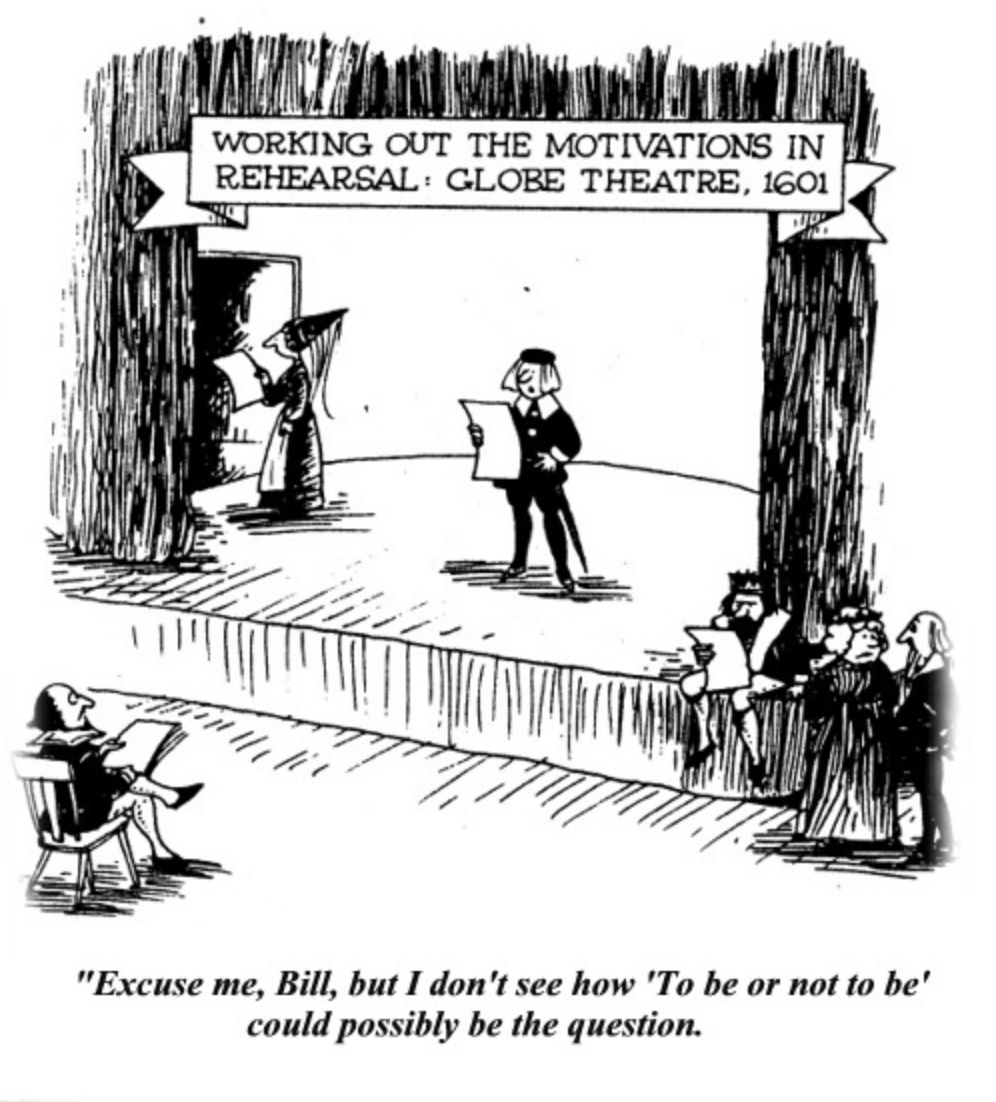

Just as we can never cover it all and must go with whatever we decide to include, we also cannot (nor should not) try to present it all, ask it all, or attempt it all in one go. Yes, the odd non sequitur can break the monotony – everyone needs a laugh, now and then. But as with all clever comedy, timing is everything, and curriculum is about more than good humour and bad logic. In that regard, given what has already been said about spotting pertinence, curriculum is about motives: to include, or not to include.

Just as we can never cover it all and must go with whatever we decide to include, we also cannot (nor should not) try to present it all, ask it all, or attempt it all in one go. Yes, the odd non sequitur can break the monotony – everyone needs a laugh, now and then. But as with all clever comedy, timing is everything, and curriculum is about more than good humour and bad logic. In that regard, given what has already been said about spotting pertinence, curriculum is about motives: to include, or not to include.