Feature Image Credit by John Manuel Kennedy Traverso on Wikipedia

Some thoughts prompted by this article by Ron Berger in EdWeek.

Early in my teaching, I decided to write prompts instead of questions. In fact, what I wrote were called imperatives or commands, a type of sentence that drops the second-person singular subject, “You,” and opens with the predicate verb:

“(You) Explain the irony of the outdoor scene from Chapter 3.”

“(You) Organise your ideas into three categories and (you) list 3–5 details beneath each one.”

“(You) Provide at least two explanations that support your conclusion.”

I decided to write prompts for two reasons. Teaching English, I wanted to practice what I preached: the verb is the most important word in a sentence. And, as a new teacher, I wanted to use Bloom’s Taxonomy because I bought into its gradual climb up the higher-order ladder, which at the time seemed to me correct.

As time went on, though, the ‘higher-order’ interpretation seemed mistaken, and was maybe fostering poorer teaching than otherwise. But I knew the importance of verbs and the power a word could have, so I started mixing so-called ‘lower-order’ commands, e.g. list, describe, explain, into ‘higher-order’ tasks and thinking, e.g. analyse, evaluate, justify. For one class, I adapted an old novel study quiz comprising uncomplicated interrogative sentences.

An inherent message to such a quiz, I felt, was essentially a teacher saying to students, “Prove that you actually read the book,” which opened up somewhat dubious questions about trust and earning grades. By rewording the quiz questions into imperatives, I wanted students to write something beyond the one-and-done sentence response.

Revising interrogative questions into imperative prompts eventually contributed to my questioning one of the structural premises behind our revised Government Curriculum, which currently emphasises skill over content. Where this Curriculum does prescribe some limited content knowledge, called “Big Ideas,” its inquiry pedagogy and student-centred approach are inherently individualised and thereby prone to opinion, which for me alters the common curricular debate over what knowledge is of most worth into a debate over whose knowledge is of most worth. Of itself, I’d say this is a worthwhile development although, in context, I think things tend to get a lot more nuanced.

So-called ‘lower-level’ skills seem no less important to me than so-called ‘higher-level’ (or the more snobbish ‘higher-order’) skills; in fact, so-called higher-order critical thinking skills depend not only on what we immediately read or hear but on what we can remember and recall from longer-term memory. And I tend to see content and skill not as discrete but integrated. To emphasise either one over the other is something akin to affixing ‘knowing’ to the bottom and ‘doing’ to the top of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

In teachers and in students, we find both the reflection of thinking and the action of doing – content as well as skill – in simultaneous tandem dynamic. To ignore their inseparability risks a curricular blunder: as skill without content is aimless, so content without skill is inert. We’re wise to conclude the same about teachers and students, who study content and skill: to each, the other is indispensible.As to those prompts I revised, students’ submissions let me know pretty quickly that they were provoking a lot more careful, imaginative thinking. Responses were detailed, thoughtful, far more personal – I knew they couldn’t be searching Google. Students often told me, “These questions are so hard,” which was honestly what I wanted to hear. I also took note that students still called them questions.

And I soon realised how much longer these responses took to read… 30min per student, 15hrs per class. I came to assigning only two prompts per chapter, and later only one, which later became “five throughout the book that you trace and develop into questions of your own.” By the time I read Ron Berger’s article, critiquing the ‘higher-order’ interpretation, my own experience was enough to confirm his assessment:

“… the root problem with [Bloom’s] framework is that it does not accurately represent the way that we learn things. We don’t start by remembering things, then understand them, then apply them, and move up the pyramid in steps as our capacity grows. Instead, much of the time we build understanding by applying knowledge and by creating things.”

Bloom’s original taxonomy has ‘knowing’ at the bottom and ‘doing’ at the top, as if to suggest that doing is contingent upon knowing. But I agree with Berger: “Every part of the framework matters, [and] teachers should instead strive for balance and integration.” Learning is neither hierarchical nor linear. If anything, as Berger mentions, we tend to create and analyse by applying what we remember in an ongoing simultaneous process. For example, consider the old adage…

I read, and I forget. I see, and I remember. I do, and I understand.

This adage is an analogy, and analogies aren’t meant to be perfect, which makes them just as instructive where their comparisons break down, showing us both what something is as well as what something is not. Ambiguity falls to context, which in turn falls at the feet of a teacher’s professional judgment: decisions really are the core of teaching.

This adage is also a simple taxonomy, one that no academic is likely to endorse – what is meant by “reading,” for example, and how is this distinguished from “seeing,” and aren’t both unique kinds of “doing”? Still, it does seem to express a bit of wisdom.

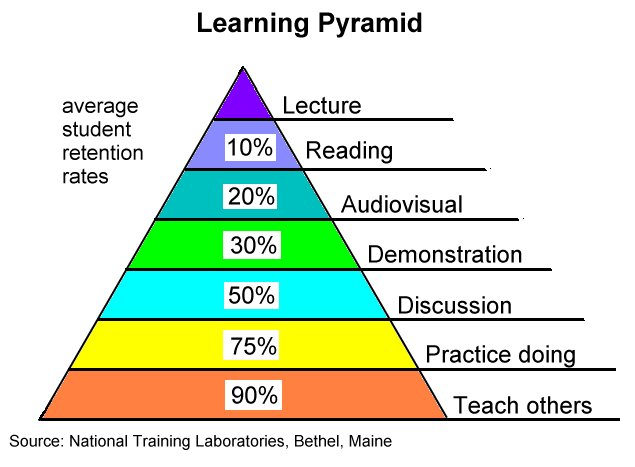

Who believes what you see? Edgar Dale’s Pyramid has been granted some pride of place in Education… looks like he must have sat through some boring lectures or something

What you may have seen from academics is something similar called the Learning Pyramid or the Cone of Experience, attributed to Edgar Dale. But don’t think that simply adding someone’s name underscores its validity or contends with other wrinkles called e-learning and machine learning.

Anyway, as an attempt to describe learning, the adage is an analogy, like Bloom’s taxonomy or any framework: fixed and rigid and literally contrived. Such things hardly represent our lived experiences although, in fairness, every perspective carries a unique set of assumptions inside its luggage.