Education is about empowering individuals to make their own decisions, and any way you slice it, individuals making decisions is how society diversifies itself. That includes diversifying the economy, as compared to the other way around.

Wanted on the Voyage: Professional Teachers are Experts in their Field

“The needs of the economy and our society are changing and therefore you need to have a learning system that fits the purpose, and that purpose is constantly shifting.”

So said Anthony Mackay, CEO of the Centre for Strategic Education (CSE) in Australia, during an interview with Tracy Sherlock from The Vancouver Sun. Mr Mackay was at SFU’s Wosk Centre for Dialogue in Vancouver on January 29, 2015, facilitating a forum about the changing face of education. Although links to the forum’s webcast archive and Sherlock’s interview are now inactive, I did save a copy of the interview text at the time, posted here beneath this essay. Tracy Sherlock has since told me that she doesn’t know why the interview’s links have been disconnected (e-mail communication, January 27, 2017). Nonetheless, there remains some on-line and pdf-print promotion and coverage of the event.

The forum and the interview were first brought to my attention via e-mail, shared by an enthusiastic colleague who hoped to spur discussion, which is altogether not an uncommon thing for teachers. Originally, I wrote distinct yet connected responses to a series of quotations from Mr Mackay’s interview. Here, some thirty-two months later, I’ve edited things into a more fluid essay although, substantively, my thoughts remain unchanged. Regrettably, so does the bigger picture.

For starters, Mr Mackay’s remark tips his hand – and that of the CSE – when he precedes society with economy. Spotting related news reports makes the idea somewhat more plausible, that of a new curriculum “…addressing a chronic skills shortage in one of the few areas of the Canadian economy that is doing well” (Silcoff)[1]. Meanwhile, in Sherlock’s interview [posted below this essay], Mr Mackay concludes by invoking “the business community,” “the economy of the future,” and employers’ confidence.

Make no mistake, Mr Mackay is as ideological as anyone out there, including me and you and everybody, and I credit him for being obvious. On the other hand, he plays into the hands of the grand voice of public educators, perhaps willfully yet in a way that strikes me as disingenuous, couched in language so positive that you’re a sinner to challenge him. Very well, I accept the challenge.

Whatever “purpose” of education Mr Mackay has in mind, here, it’s necessarily more specific unto itself than to any single student’s interests or passions. In other words, as I take his portrayal, some student somewhere is a square peg about to be shown a round hole. Yet this so-called purpose is also “constantly shifting,” so perhaps these are triangular or star-shaped holes, or whatever, as time passes by.

Enter “discovery learning” – by the way, are we in classrooms, or out-and-about on some experiential trip? – and the teacher says only what the problem is, leaving the students to, well, discover the rest. I can see where it has a place; how it enables learning seems obvious enough since we learn by doing – teach someone to fish, and all. But when it comes to deciding which fish to throw back, or how many fish are enough when you don’t have a fridge to store them in before they rot and attract hungry bears… when it comes to deciding what’s more versus less important, those minutiae of mastery, it’s not always as easy as an aphorism or a live-stream video conference.

Where it’s more hands-off from the teacher, in order to accommodate the student, discovery learning seems to me better suited to learners well past any novice stage. And if the teacher said, “Sorry, that’s not discovery learning,” would the students remain motivated? Some would; others most certainly would not: their problem, or the teacher’s? When both the teacher and the students say, “We really do need to follow my lead just now,” which party needs to compromise for the other, and to what extent? Teaching and learning ought to be a negotiation, yes, but never an adversarial one. In the case of “discovery learning,” I wonder whether “teacher” is even the right title anymore.

In any case, Mr Mackay appears guilty of placing the cart before the horse where it comes to educating students according to some systemic purpose. I’ve got more to say, below, about this particular detail, what he calls “personalization.” For now, it’s worth setting some foundation: Ken Osborne wrote a book called Education, which I would recommend as a good basis for challenging Mr Mackay’s remarks from this interview.

That Osborne’s book was published in 1999 I think serves my point, which is to say that discernment, critical thinking, effective communication, and other such lauded “21st century skills” were in style long before the impending obscurity of the new millennium. They have always offered that hedge against uncertainty. People always have and always will need to think and listen and speak and read, and teachers can rely on this. Let’s not ever lose sight of literacy of any sort, in any venue. Which reminds me…

That Osborne’s book was published in 1999 I think serves my point, which is to say that discernment, critical thinking, effective communication, and other such lauded “21st century skills” were in style long before the impending obscurity of the new millennium. They have always offered that hedge against uncertainty. People always have and always will need to think and listen and speak and read, and teachers can rely on this. Let’s not ever lose sight of literacy of any sort, in any venue. Which reminds me…

“Isn’t that tough when we don’t know what the jobs of the future will be?”

I must be frank and admit… this notion of unimaginable jobs of the future never resonated with me. I don’t remember when I first heard it, or even who coined it, but way-back-whenever, it instantly struck me as either amazing clairvoyance or patent nonsense. I’ve heard it uttered umpteen times by local school administrators, and visiting Ministry staff, and various politicians promoting the latest new curriculum. The idea is widely familiar to most people in education these days: jobs of the future, a future we can’t even imagine! Wow!

Well, if the unimaginable future puzzles even the government, then good lord! What hope, the rest of us? And if the future is so unimaginable, how are we even certain to head any direction at all? When you’re lost in the wilderness, the advice is to stay put and wait for rescue. On the other hand, staying put doesn’t seem appropriate to this discussion; education does need to adapt and evolve, so we should periodically review and revise curricula. But what of this word unimaginable?

For months prior to its launch, proponents of BC’s new curriculum clarified – although, really, they admonished – that learning is, among other things, no longer about fingers quaintly turning the pages of outmoded textbooks. To paraphrase the cliché, that ship didn’t just sail, it sank. No need to worry, though. All aboard were saved thanks to new PDFs– er, I mean PFDs, personal floatation devices– er, um, that is to say personal floatation e-devices, the latest MOBI-equipped e-readers, to be precise. As for coming to know things (you know, the whole reason behind “reading” and all…), well, we have Google and the Internet for everything you ever did, or didn’t, need to know, not to mention a 24/7 news cycle, all available at the click of a trackpad. It’s the 21st century, and learning has reserved passage aboard a newer, better, uber-modern cruise ship where students recline in ergonomic deck chairs, their fingertips sliding across Smart screens like shuffleboard pucks. Welcome aboard! And did I mention? Technology is no mere Unsinkable Ship, it’s Sustainable too, saving forests of trees from the printing press (at a gigawatt-cost of electricity, mind, but let’s not pack too much baggage on this voyage).

Sorry, yes, that’s all a little facetious, and I confess to swiping as broadly and inaccurately as calling the future “unimaginable.” More to the point: for heaven’s sake, if we aren’t able to imagine the future, how on earth do we prepare anybody for it? Looking back, we should probably excuse Harland & Wolff, too – evidently, they knew nothing of icebergs. Except that they did know, just as Captain Smith was supposed to know how to avoid them.

But time and tide wait for no one which, as I gather, is how anything unimaginable arose in the first place. Very well, if we’re compelled toward the unknowable future, a cruise aboard the good ship Technology at least sounds pleasant. And if e-PFDs can save me weeks of exhausting time-consuming annoying life-skills practice – you know, like swimming lessons – so much the better. Who’s honestly got time for all that practical life-skills crap, anyway, particularly when technology can look after it for you – you know, like GPS.

If the 21st century tide is rising so rapidly that it’s literally unimaginable (I mean apart from being certain that we’re done with books), then I guess we’re wise to embrace this urgent… what is it, an alert? a prognostication? guesswork? Well, whatever it is, thank you, Whoever You Are, for such vivid foresight– hey, that’s another thing: who exactly receives the credit for guiding this voyage? Who’s our Captain aboard this cruise ship? IT Departments might pilot the helm, or tend the engine room, but who’s the navigator charting our course to future ports of call? And where’s our destination? Even the most desperate voyage has a destination; I wouldn’t even think a ship gets built unless it’s needed. Loosen your collars, everybody, it’s about to get teleological in here.

Q: What destination, good ship Technology?

A: The unknowable future…

Land?-ho! The Not-Quite-Yet-Discovered Country… hmm, would that be 21st century purgatory? Forgive my Hamlet reference – it’s from a mere book.

To comprehend the future, let’s consider the past; history can be instructive. Remember that apocryphal bit of historical nonsense, that Christopher Columbus “discovered America,” as if the entire North American continent lay indecipherably upon the planet, unbeknownst to Earthlings? (Or maybe you’re a 21st century zealot who only reads blogs and Twitter, I don’t know.) Faulty history aside, we can say that Columbus had an ambitious thesis, a western shipping route to Asia, without which he’d never have persuaded his political sponsors to back the attempt. You know what else we can say about Columbus, on top of his thesis? He also had navigation and seafaring skill, an established reputation that enabled him to approach his sponsors in the first place. As a man with a plan to chart the uncharted, even so Columbus possessed some means of measuring his progress and finding his way. In that respect, it might be more accurate to say he earned his small fleet of well-equipped ships. What history then unfolded tells its own tale, the point here simply that Columbus may not have had accurate charts, but he also didn’t set sail, clueless, to discover the unimaginable in a void of invisible nowhere.

But what void confronts us? Do we really have no clue what to expect? To hear the likes of Mackay tell it, with technological innovation this rapid, this influential, we’re going to need all hands on deck, all eyes trained forward, toward… what exactly? Why is the future so unimaginable? Here’s a theory of my very own: it’s not.

Discovering in the void might better describe Galileo, say, or Kepler, who against the mainstream recharted a mischarted solar system along with the physics that describe it. Where they disagreed over detail, such as ocean tides (as I gather, Kepler was right), they each had pretty stable Copernican paradigms, mediated as much by their own empirical data as by education. Staring into the great void, perhaps these astronomers didn’t always recognise exactly what they saw, but they still had enough of the right stuff to interpret it. Again, the point here is not about reaching outcomes so much as holding a steady course, and having the skill to do so. Galileo pilots himself against the political current and is historically vindicated on account of his curious mix of technological proficiency, field expertise, and persistent vision. For all that he was unable to predict or fully understand, Galileo still seemed to know where he was going.

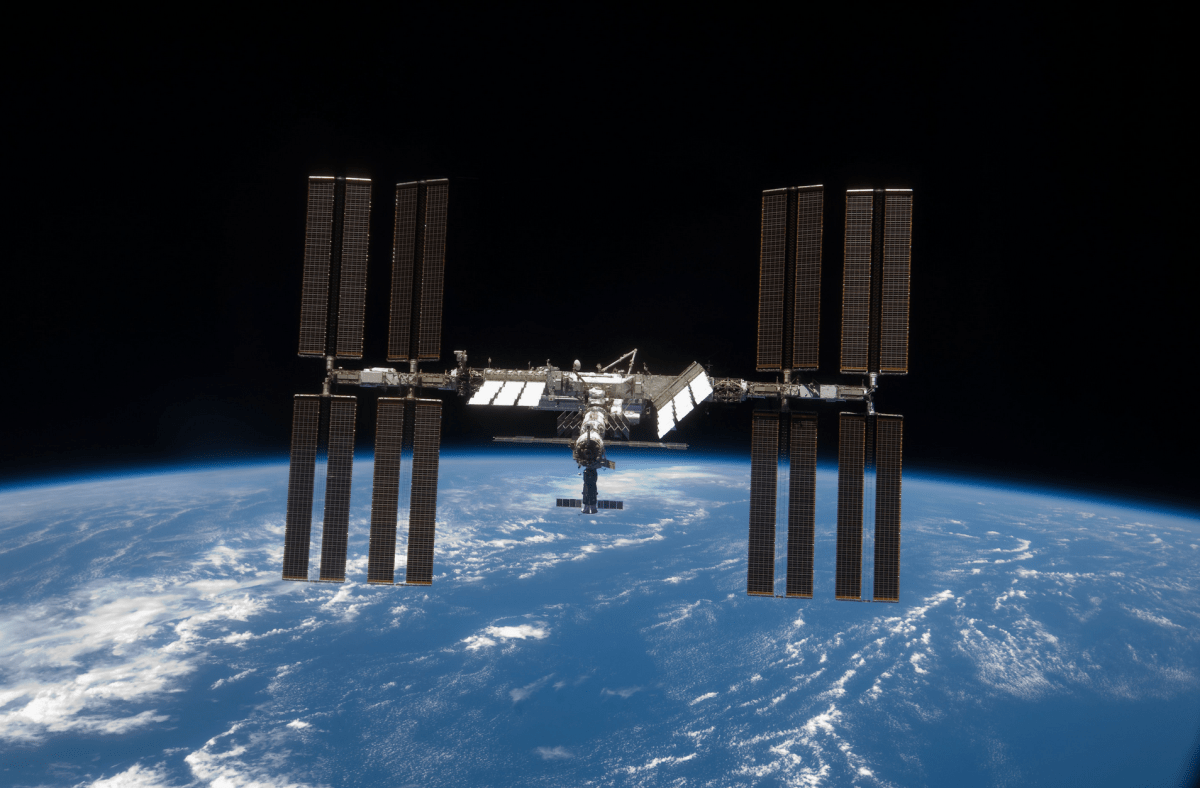

I suppose if anyone might be accused of launching speculative missions into the great void of invisible nowhere, it would be NASA, but even there is clarity. Just to name a few: Pioneer, Apollo, Voyager, Hubble – missions with destinations, destinies, and legacies. Meanwhile, up in the middle of Nowhere, people now live in the International Space Station. And hang on because NASA doesn’t launch people into space willy-nilly. It all happens, as it should, and as it must, in a context with articulated objectives. Such accomplishments do not arise because the future is unimaginable; on the contrary, they arise precisely because people are able to imagine the future with pretty astounding precision.

Which brings me back to Mr Mackay and the government’s forum on education. It’s not accurate for me to pit one side against another when we all want students to succeed. If I’ve belaboured the point here, it’s because our task concerns young people. Selling those efforts as some blind adventure seems, to me, the height of irresponsibility wrapped in an audacious marketing campaign disguised as an inevitable future, a ship setting sail so climb aboard, and hurry! Yes, I see where urgency is born of rapid innovation, technological advancement made obsolete mere weeks or months later. For some, I know that’s thrilling. For me, it’s more like the America’s Cup race in a typhoon: thanks, but no thanks, I’ll tarry ashore a while longer, in no rush to head for open sea, not even aboard a vaunted ocean liner.

We simply mustn’t be so eager to journey into the unknown without objectives and a plan, not even accompanied as we are by machines that contain microprocessors, which is all “technology” seems to imply nowadays. There’s the respect that makes calamity of downloading the latest tablet apps, or what-have-you, simplistically simply because the technology exists to make it available. How many times have teachers said the issue is not technology per se so much as knowing how best to use it? Teleology, remember – what exactly is it for, or who? By the way, since we’re on the subject, what is the meaning of life? One theme seems consistent: the ambition of human endeavour. Sharpen weapon, kill beast. Discover fire, cook beast! Discover agriculture, domesticate beast. Realise surplus, and follows world-spanning conquest of culture eventually reach for stars.

Look, if learning is no longer about fingers quaintly turning the pages of outmoded textbooks, then fine. I still have my doubts – I’ve long said vinyl sounds better – but let that go. Can we please just drop the bandwagoning and sloganeering, and get more specific? By now, I’ve grown so weary of “the unimaginable future” as to give it the dreaded eye-roll. And if I’m a teenaged student, as much as I might be thrilled by inventing jobs of the future, I probably need to get to know me, too, who and what I’m all about.

In truth, educators do have one specific aim – personalized learning – which increasingly has come into curricular focus. Personalization raises some contentious issues, not least of which is sufficient funding since the need for individualized attention requires more time and resources per student. Nevertheless, it’s a strategy that I’ve found positive, and I agree it’s worth pursuing. That brings me back to Ken Osborne. One of the best lessons I gathered from his book was the practicality of meeting individuals wherever they reside as compared to determining broader needs and asking individuals to meet expectations.

Briefly, the debate presents itself as follows…

- Side ‘A’ would determine communal needs and educate students to fill the roles

In my humble opinion, this is an eventual move toward social engineering and a return to unpleasant historical precedent.

- Side ‘B’ would assess an individual’s needs and educate a student to fulfil personal potential

In my humble opinion, this is a course that educators claim to follow everyday, especially these days, and one that they would do well to continue pursuing in earnest.

In my experience, students find collective learning models to be less relevant and less authentic than the inherent incentives found in personalized approaches that engender esteem and respect. Essentially, when we educate individuals, we leave them room to sort themselves out and accord them due respect for their ways and means along the way. In return, each person is able to grasp the value of personal responsibility. Just as importantly, the opportunity for self-actualisation is now not only unfettered but facilitated by school curricula, which I suspect is what was intended by all the “unimaginable” bluster in the first place. The communal roles from Osborne’s Side ‘A’ can still be filled, now by sheer numbers from the talent pool rather than by pre-conceived aims to sculpt square pegs for round holes.

Where I opened this essay with Anthony Mackay’s purposeful call to link business and education, I’ve been commenting as a professional educator because that is my field, so that is my purview. In fairness to government, I’ve found that more recent curricular promotion perhaps hints at reversing course from the murk of the “unimaginable” future by emphasizing, instead, more proactive talk of skills and empowerment.

Communal roles can be filled by sheer numbers from the talent pool rather than by pre-conceived aims to sculpt square pegs for round holes

Even so, a different posture remains (touched upon in Katie Hyslop’s reporting of the forum and its ostensible participants, and a fairly common discursive thread in education in its own right), one that implicitly conflates the aims of education and business, and even the arts. Curricular draft work distinguishes the “world of work” from details that otherwise describe British Columbia’s “educated citizen” (p. 2). [2] Both Ontario and Alberta’s curricular plans have developed comparably to BC’s, with Alberta noting employers’ rising expectations that “a human capital plan” will address our ever-changing “world of work” (p. 5)[3] – it’s as if school’s industrial role were a given. Credit where it’s due, I suppose: they proceed from a vision towards a destination. And being neither an economist nor an industrialist, I don’t aim to question the broader need for business, entrepreneurship, or a healthy economy. Everybody needs to eat.

What I am is a professional educator, and that means I have been carefully and intentionally educated, mentored, and accredited alongside my colleagues to envision, on behalf of all, what is best for students. So when I read a claim like Mr Mackay’s, that “what business wants in terms of the graduate is exactly what educators want in terms of the whole person,” I am wary that his educational vision and leadership are yielding our judgment to interests, such as commerce and industry, that lie beyond the immediately appropriate interests of students. Anthony Mackay demonstrates what is, for me, the greatest failing in education: leaders whose faulty vision makes impossible the very aims they set out to reach. (By the by, I’ve also watched such leadership condemn brilliant teaching that reaches those aims.) As much as a blanket statement, Mr Mackay makes an unfounded statement, and I could hardly do better to find an example of begging the question. If Mr Mackay is captain of this ship, then maybe responsible educators should be reading Herman Wouk – one last book, sorry, couldn’t resist.

Education is about empowering individuals to make their own decisions, and any way you slice it, individuals making decisions is how society diversifies itself. That includes diversifying the economy, as compared to the other way around (the economy differentiating individuals). Some people are inevitably more influential than others. All the more reason then for everybody, from captains of industry on down, to learn to accept responsibility for respecting an individual by clearing some space, even while everybody learns to decide what course to ply for themselves. Personalized learning is the way to go as far as resources can be distributed, so leave that to the trained professional educators who are entrusted with the task, who are experts at reading the charts, spotting the hazards, and navigating the course, even through a void. Expertise is a headlight, or whatever those are called aboard ships, so where objectives require particular expertise, let us be lead by qualified experts.

And stop with the nonsense. No unimaginable future “world of work” should be the aim of students to discover while their teachers tag along like tour guides. Anyway, I thought the whole Columbus “discovery” thing had helped us to amend that sort of thinking, or maybe I was wrong. Or maybe the wrong people decided to ignore history and spend their time, instead, staring at something they convinced themselves was impossible to see.

3 February 2015

Vancouver Sun Weekday Sample

Tracy Sherlock VANCOUVER SUN View a longer version of this interview at vancouversun.com Sun Education Reporter tsherlock@vancouversun.com

Changing education to meet new needs

“The learning partnership has gotto go beyond the partnership of young person and family, teacher and school, to the community and supportive agencies.

TONY MACKAY CEO, CENTRE FOR STRATEGIC EDUCATION IN AUSTRALIA

Tony Mackay, CEO at the Centre for Strategic Education in Australia, was in Vancouver recently, facilitating a forum about changing the education system to make it more flexible and personalized. He spoke about the rapidly changing world and what it means for education.

Q Why does the education system need to change?

A The needs of the economy and our society are changing and therefore you need to have a learning system that fits the purpose, and that purpose is constantly shifting. So it’s not just a matter of saying we can reach a particular level and we’ll be OK, because you’ve got such a dynamic global context that you have a compelling case that says we will never be able to ensure our ongoing level of economic and social prosperity unless we have a learning system that can deliver young people who are ready — ready for further education, ready for the workforce, ready for a global context. That’s the compelling case for change.

Q Isn’t that tough when we don’t know what the jobs of the future will be?

A In the past we knew what the skill set was and we could prepare young people for specialization in particular jobs. Now we’re talking about skill sets that include creativity, problem solving, collaboration, and the global competence to be flexible and to have cultural understanding. It’s not either or, it’s both and — you need fantastic learning and brilliant learning in the domains, which we know are fundamental, but you also need additional skills that increasingly focus on emotional and social, personal and inter-personal, and perseverance and enterprising spirit. And we’re not saying we just want that for some kids, we want to ensure that all young people graduate with that skill set. And we know they’re going to have to effectively “learn” a living — they’re going to have to keep on learning in order to have the kind of life that they want and that we’re going to need to have an economy that thrives. I believe that’s a pretty compelling case for change.

Q How do you teach flexibility?

A When I think about the conditions for quality learning, it’s pretty clear that you need to be in an environment where not only are you feeling emotionally positive, you are being challenged — there’s that sense that you are challenged to push yourself beyond a level of comfort, but not so much that it generates anxiety and it translates into a lack of success and a feeling of failure that creates blockages to learning. You need to be working with others at the same time — the social nature of learning is essential. When you’re working with others on a common problem that is real and you have to work as a team and be collaborative. You have to know how to show your levels of performance as an individual and as a group. You can’t do any of that sort of stuff as you are learning together without developing flexibility and being adaptive. If you don’t adapt to the kind of environment that is uncertain and volatile, then you’re not going to thrive.

Q What does the science of learning tell us?

A We now know more about the science of learning than ever before and the question is are we translating that into our teaching and learning programs? It’s not just deeper learning in the disciplines, but we want more powerful learning in those 21st-century skills we talked about. That means we have to know more than ever before about the emotions of learning and how to engage young people and how young people can encourage themselves to self-regulate their learning.

The truth is that education is increasingly about personalization. How do you make sure that an individual is being encouraged in their own learning path? How do we make sure we’re tapping into their strengths and their qualities? In the end, that passion and that success in whatever endeavour is what will make them more productive and frankly, happier.

Q But how do you change an entire education system?

A Once you learn what practice is done and is successful, how do you spread that practice in a school system so it’s not just pockets of excellence, but you’ve actually got an innovation strategy that helps you to spread new and emerging practice that’s powerful? You’re doing this all in the context of a rapidly changing environment, which is why you need those skills like flexibility and creativity. The learning partnership has got to go beyond the partnership of young person and family, teacher and school, to the community and supportive agencies. If we don’t get the business community into this call to action for lifelong learning even further, we are not going to be able to get there. In the end, we are all interdependent. The economy of the future — and we’re talking about tomorrow — is going to require young people with the knowledge, skills and dispositions that employers are confident about and can build on.

Previously available at http://www.pressreader.com/canada/the-vancouver-sun/20150203/282183649467268/TextView

and http://newsinvancouver.com/qa-changing-education-to-meet-new-needs/

[1] Sean Silcoff, The Globe and Mail, BC to add computer coding to school curriculum (Jan 17th, 2016)

[2] Introduction to British Columbia’s Redesigned Curriculum (August 2015 – Draft)

[3] Inspiring Action on Education (June 2010)