Click here to read Pt. III Craft Displacement

IV. Grounding Movement Control

“I think what we’re learning is that, particularly when they get a choice, a lot of people decide to believe what’s more comfortable for them, even if it’s not the truth.”

– Ellis Cose

We’ve always lived with both truth and lies. Concern today, arising directly from how ubiquitous they are, truth and lies, is how competitive they are. And how rapidly they spread.

I’ve sometimes thought “social media” should be renamed social immediate… social’s a bit generous, I think, altruistic, but of course it’s media and immediate, sharing common etymology, that are more than just clever word-play.

On-line life began like any new relationship… a little mysterious, a little enchanted. Since those early days, we live so much of our lives on screens… how are we coping with the reach and pace of this on-line world, its arbitrary spread of content that people decide to believe, that “gives the illusion of consensual validation”? How are we affording ourselves “sufficient time to avert the evil consequences of noxious doctrine by argument and education”? How are we reckoning with the access and clout marshalled to special advantage by a privileged few? By how, I mean intentionally how?

These are hardly questions to be glossed over, especially when we use the very same lightspeed reach and pace for argument and education. We seem to be building the plane while learning to be the pilot while also issuing boarding passes and studying for our tower badge while flying. On top of all this, what the tower calls a landing strip some pilots believe is a mirage, if not flat-out deception.

It’s very difficult to say on what grounds something is hate speech and who should make that decision because some people find Zionism hate speech. Some people find Black Lives Matter hate speech. It’s easy to use the phrase ‘hate speech,’ but it means different things to different people, even people who think they know what it is when they see it.

Ellis Cose

By the way, if you’re thinking just now, “Yes, it’s awful how quickly lies spread,” well, it’s possible the liars are thinking the same thing. Maybe you’re now spotting the same problem as me… two wrongs don’t make a right, and yes, it’s a different way to think of the two wrongs, owned one each per ‘side’ – just to clarify, this would be both sets of ‘liars’ sharing responsibility to connect, or else clash. So yes, it’s a bit different, and it’s definitely no cause for censorious scorn or sanctimonious virtue-signalling – I mean, unless everyone wants the fighting to continue. And if that redoubles your indignation, well, very likely it’s doubled theirs, too, and here we all are, equal by at least one measure.

We all lay claim to weighty title-deeds; but as any physicist will tell you, weight is commonly misapprehended, and the question, really, is over whose voices bear sufficient persuasive mass to tamp the rest of us down within their gravity well, and whose would have us believe we’re defying gravity.

And here is the heart of Cose’s counsel: truth is not driving out lies.

As I say, it’s competing with them. Cose takes himself to be justified on the ‘side’ of truth – fair enough, we all have our convictions; for the record, I agree with him. In this post, however, I’m trying more clinically just to observe the conflict, which seems as protracted for a liar as for anyone since driving out lies with truth precludes no truth that any ‘side’ might wield. If that’s not a debate toward persuasion, it can still be a battle to the death.

Yes, “speech may be fought with speech,” but how effective is it when people’s beliefs on the same planet have become separate world ideologies? And when government, for the public, has no claim to control what somebody, in private, decides they want silenced, just who gets to say who gets to say? From having earlier considered the speaker, and the speech they profess, we’re now unquestionably trolling the realm of the audience.

And that audience has a setting, whether a venue or some medium, which itself is part of a larger culture, etc etc, blah blah blah… and if appreciating all this ‘in context’ seems obvious, then ask yourself why we still dispute free speech? To borrow an earlier phrase, it’s hard to blame the craft when it’s the artisan.

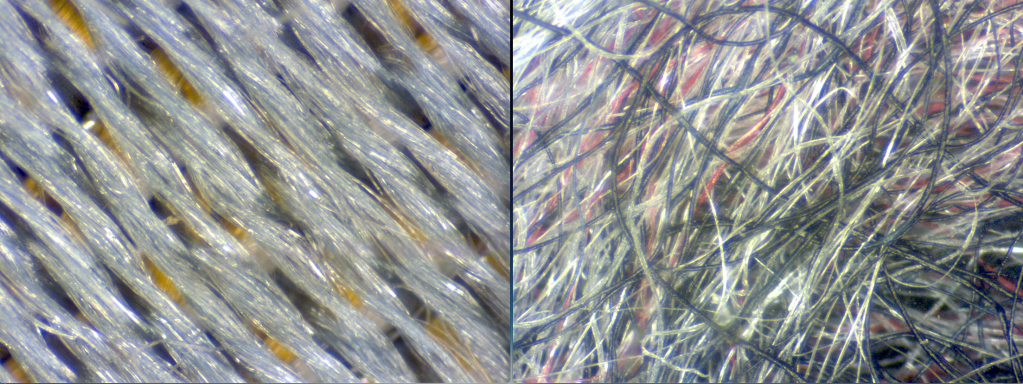

Free speech per se is a concept, and it’s one thing to aspire to values. But it’s quite another to assume them, and we don’t live in a Land of Should, where the statues talk and live among us, and concepts send us greeting cards embossed with dogma. As we’re now considering audience, we’re no longer considering only the person who speaks, or only their speech, or only the venue in which they speak. We’re also beyond one audience’s concerns, or one cultural setting, or even cultures colliding: free speech enacted is all of the above. Like loose strands in a weave, pulling one means the rest come with it. To do it any justice obliges us to consider free speech not in the immediacy of one person’s freedom but as an ongoing social gathering, or convergence. Free speech per se is one thing; free speech enacted is quite another.

At issue is not free speech per se but our e-tech immediacy, so vastly more efficient than ever before, with a widespread audience to match.

At issue are the people in that audience, and their coping strategies: discernment, tolerance, critical thinking, an ability to hold in mind two contradictory ideas, or at least more than one comfortable idea.

At issue are ideology and the “immediate interests [that] exercise a kind of hydraulic pressure which makes what previously was clear seem doubtful”… all the ‘should’ that wants to last and grow and protect and endure by carving a comfortable niche.

At issue is our patience, and our willingness to distinguish nuance, and our susceptibility to emotion, as part or separate from reason – that’s on you and me both, and sorry for getting in your face about it, but while we’re on you, what exactly do you make of the speaker’s character? Because that’s no longer just you; that’s both you and the speaker. Cyclical, mutual, together. This is a joint effort.

I consider the nuances of free speech with the three rhetorical appeals and wonder at some error in the sonorous formula by which one person, like one appeal, is raised to matter above all else. In the so-called digital age, what lies between the echo chambers is less a public forum than the contested battleground of a fight that is less about some freely spoken topic than who shall freely speak. When I hear people invoke “free speech” as targeting anticipated outcomes or effects of speech rather than addressing the catalyst or cause of speech, I wonder if their judgment has already been passed. I wonder if the speaker’s credibility is simply ad hominem in waiting – it’s not always so, but I wonder at the possibility, at the sure traction we seek on the slippery slopes we grade.

I wonder if an entire audience has had its capacity assumed, in lieu of their involvement, by a few of its more vigilant assertive presumptive strident zealous clamorous… – by ideologues… – by a few of its members. In fairness, what one may call advocacy another might call oppression; just as what one may call disinterest, another might call complicity; or as differently educated, ignorant or uninformed. Yet no impasse need be permanent unless we’re willing – is it obstinacy that makes you so parochial, or integrity? When is refusal a sign of conviction, and when is it just being lazy?

We possess no freedom – neither active freedom to nor passive freedom from – that is not without corresponding cost; we live alongside others whose freedoms, like our own, ought not to be denied.

And we bear no right that does not oblige concomitant responsibility to others; apart from others, what stipulation of freedoms or rights is even necessary?

All well and good, but when are principled statements ever more than mere words? And if you say, “Rule of law…” I’ll reply, “… yes, and lawbreakers.” High statements about rights and freedoms are symbolic, nothing more. Respect for the rule of law is realised behaviour, enacted decisions, and real consequences; words, like statues and sculptures, only depict and describe. True, there’s yet to say “self-discipline,” “community,” and “education,” or how about “enforcement,” but free speech per se remains a concept, nothing more.

Free speech enacted is more complex. It’s not about the one who’s angered and vocal, it’s not about the one who’s squeamish and militant, it’s not about any one at all whom we might try to describe as a speaker or a listener – free speech is not about any one, but always at least two, and far more likely even more. Free speech, like every freedom and right we boast, demands as much give as take. If that balance is contextual, it’s also never only one person toeing its edge.

At last we’ve landed in a place to offer the trite-and-true “words matter”: indeed, words do matter, in a demonstrable, consequential, fundamental way. They matter, just like the people who use them – or rather because it is people who use them.

Words matter because people matter, yet we protect and prize our free speech distinctly inside the public sphere versus outside. Prohibiting government from restricting our free speech, based on its content, is its own defining characteristic: it is based on past experience and, you might say, ought to speak for itself. In other words, protecting our speech, with some granted qualifications, from government interference was an intentional decision.

Curious that we might find similar…? intent in the private sphere, except here the intent seems…? to restrict free speech, and it arises among people who evidently privilege themselves…? as a kind of alternative government without prohibition. Quite apart from choosing to not listen to free speakers, such people proclaim a mandate on behalf of the rest of us to silence them. Who among us may justifiably enact this distinction? Whomever already does.

Click here to read the final post in this series on free speech: Part V. Bending Two Extremes.